In the sixteenth century, the powerful Medici family dominated life in Florence. Their influence extended as far as Rome. The defence of their sovereignty went hand in hand with intrigues, armed conflicts and citizens’ revolts. The Florentine bankers’ family strongly supported culture and the arts in their city.

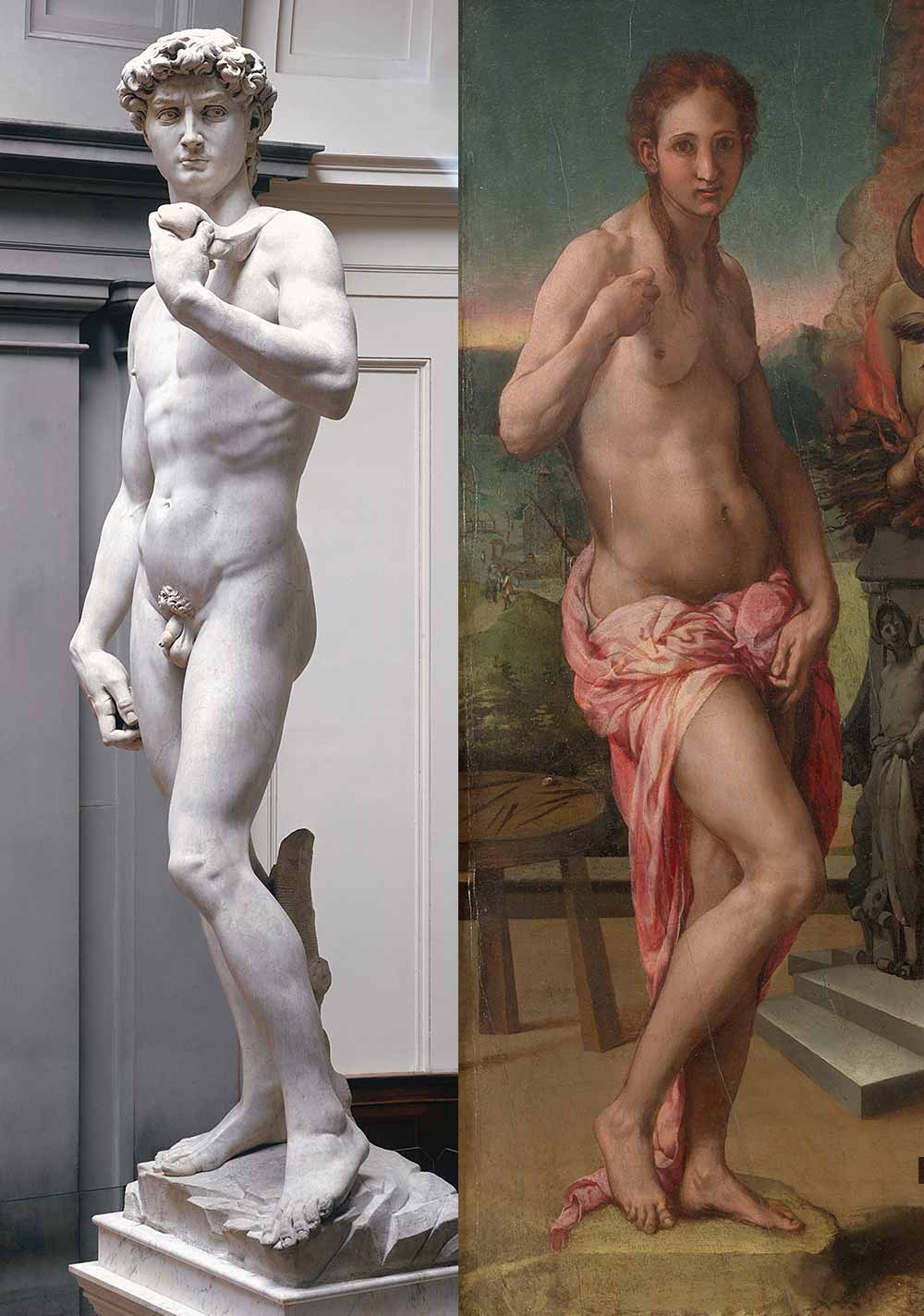

In this productive phase, painters such as Pontormo, Bronzino, Rosso Fiorentino and Vasari developed new artistic approaches. They experimented in their works with refined – and sometimes bizarre – forms, colours and compositions. They thus emancipated themselves from their famous predecessors of the Italian High Renaissance.

Now these artists are making their first major appearance in Germany: in 120 spectacular loans, Mannerism impressively presents itself as a style both fascinating and multifaceted.

The stylish

style

These delicate hands were not made for working. The young man elegantly bends his long, slender fingers. His pale skin contrasts with his dark clothing. In his left hand he nonchalantly holds a pair of expensive leather gloves – a luxury good in sixteenth-century Florence.

Practise in everything a certain nonchalance that shall conceal design and show that what is done and said is done without effort and almost without thought.1

Baldassare Castiglione, The Book of the Courtier, 1528

Mise-en-scène

The young lady casually directs her gaze directly at the viewer. Nevertheless, no real sense of closeness comes about. Her smooth, calm face reveals nothing of what is going on in her mind and heart. In contrast, her vivid red dress with its voluminous puffy sleeves radiates vibrant energy. Is it a spirited personality that lies concealed behind this cool façade?

Elongated faces

with dark eyes

The well-known biographer and painter Giorgio Vasari wrote of the artist Rosso Fiorentino that he “would study art with but few masters, having a certain opinion of his own that conflicted with their manners”. 2

Paintings of the Madonna

Depictions of the Virgin and Child with the Infant St John were extremely popular in sixteenth-century Florence. They show Mary holding her son Jesus in her arms, accompanied by John, who will later baptize Christ.

The allure

of experimentation

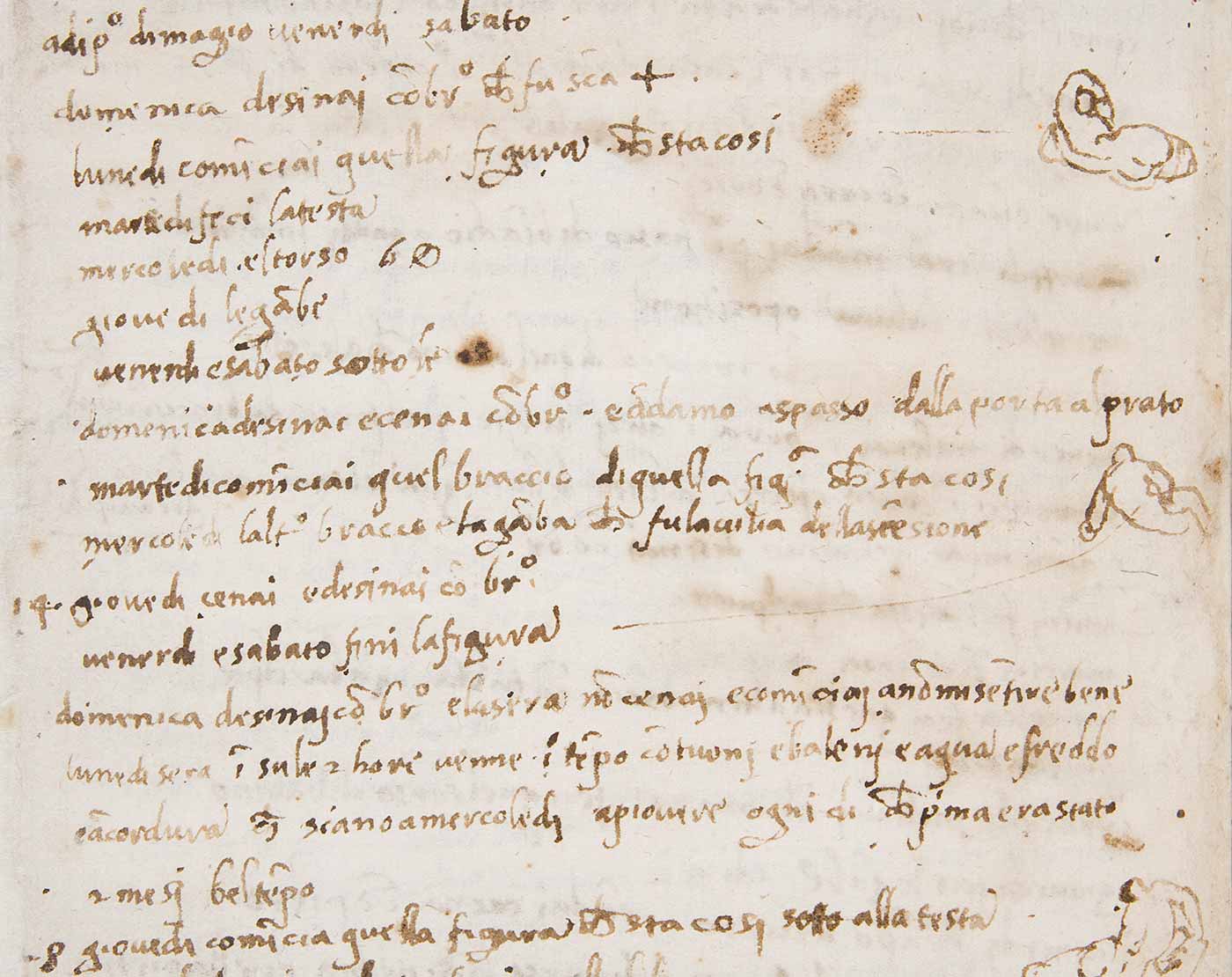

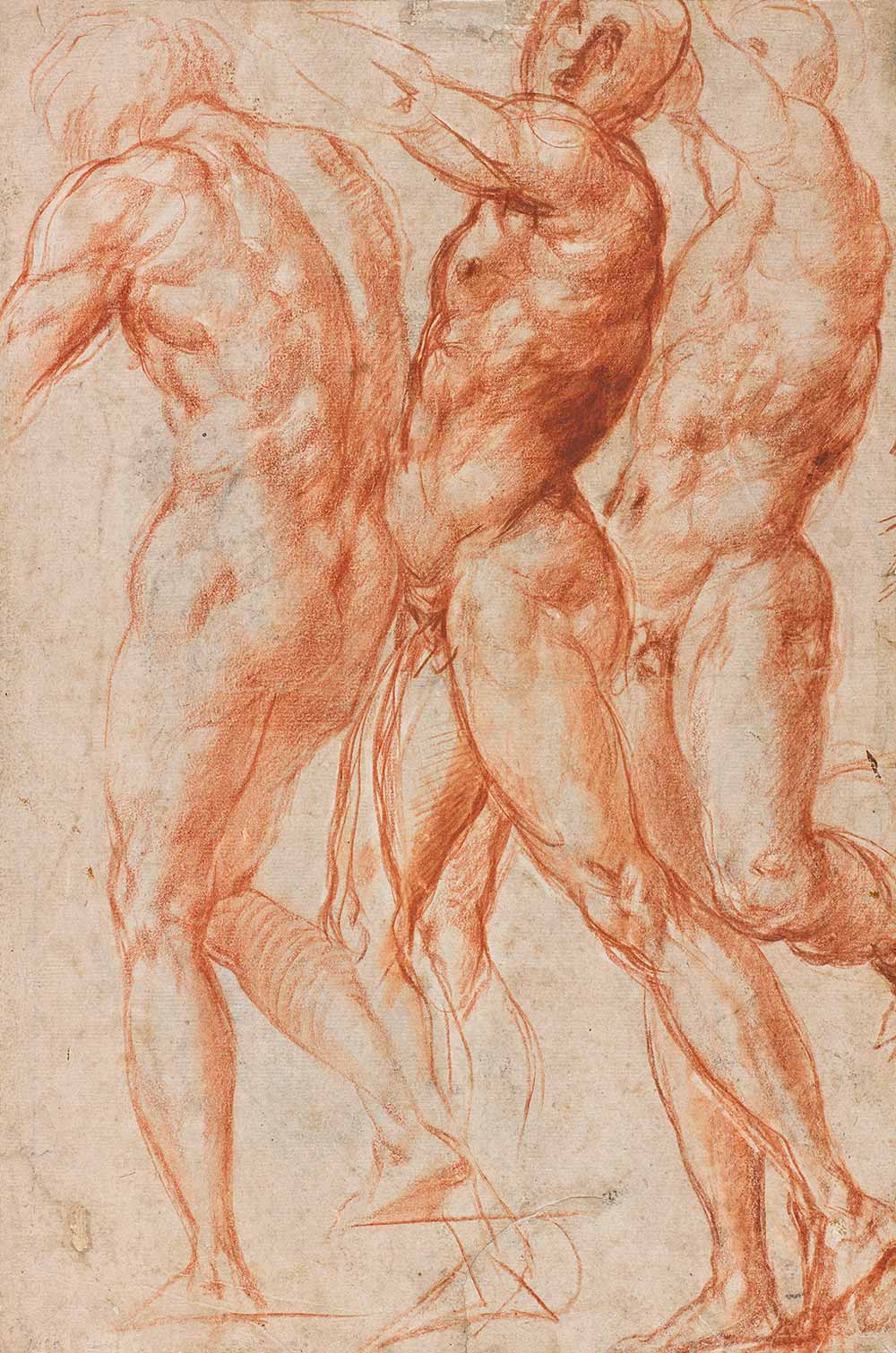

The challenge of departing from existing rules of beauty and harmony ‒ or of developing them further ‒ appealed to the Florentine Mannerists. Their enthusiasm for artistic experimentation resonates above all in their drawings and sketches.

Animated lines

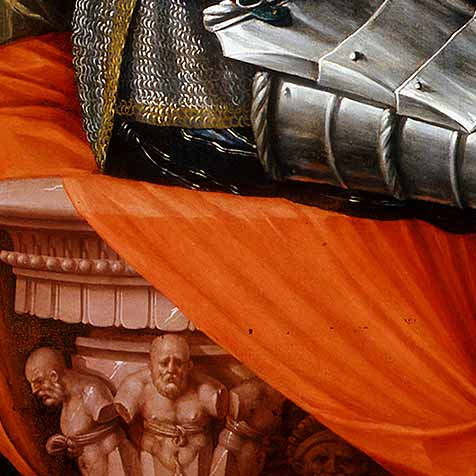

This drawing may remind the modern viewer of photographic series depicting motion sequences. Jacopo Pontormo, however, was experimenting with various poses of a naked male body.

Contorted bodies

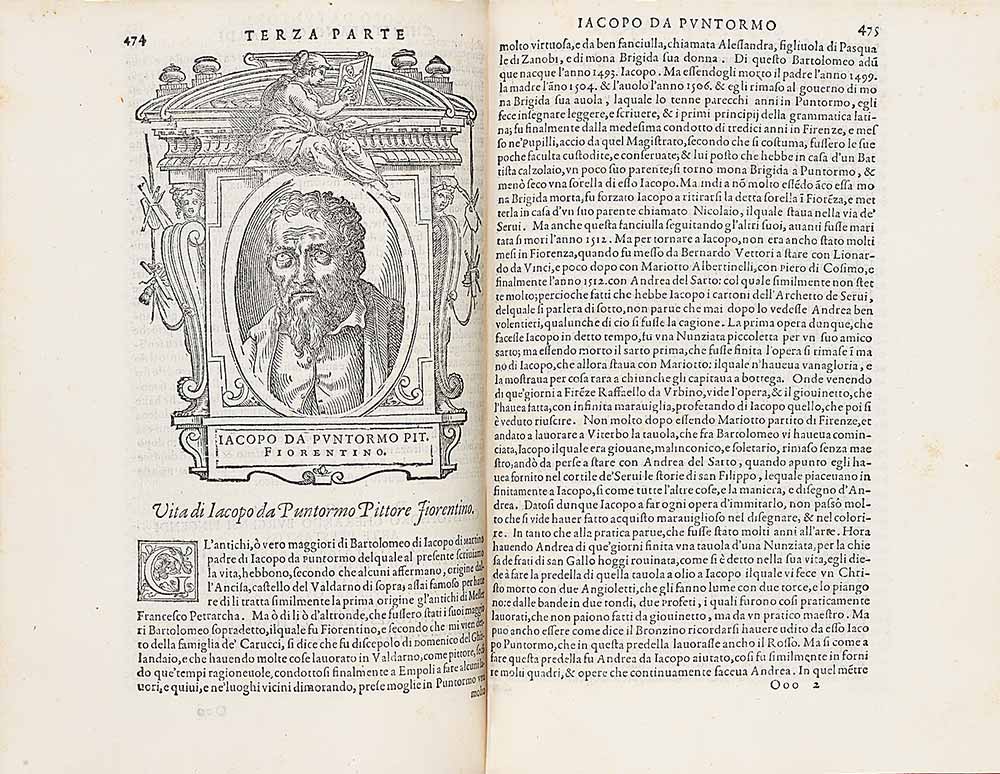

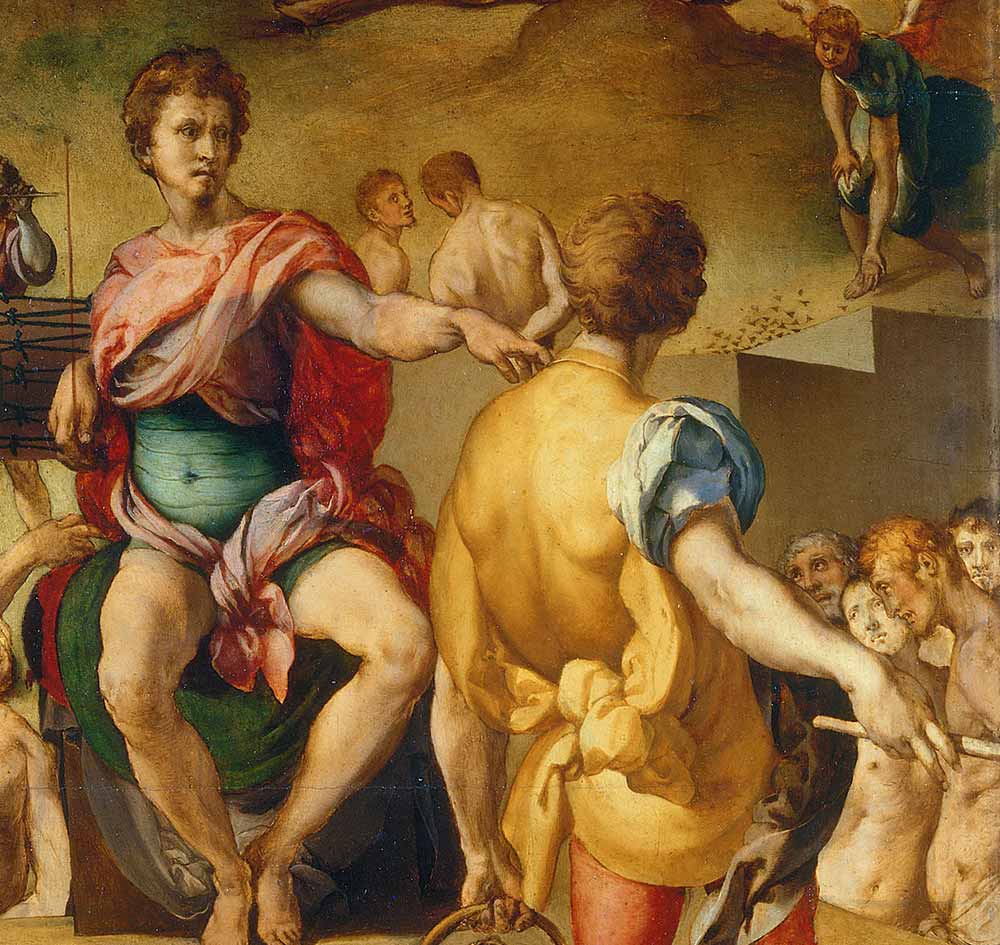

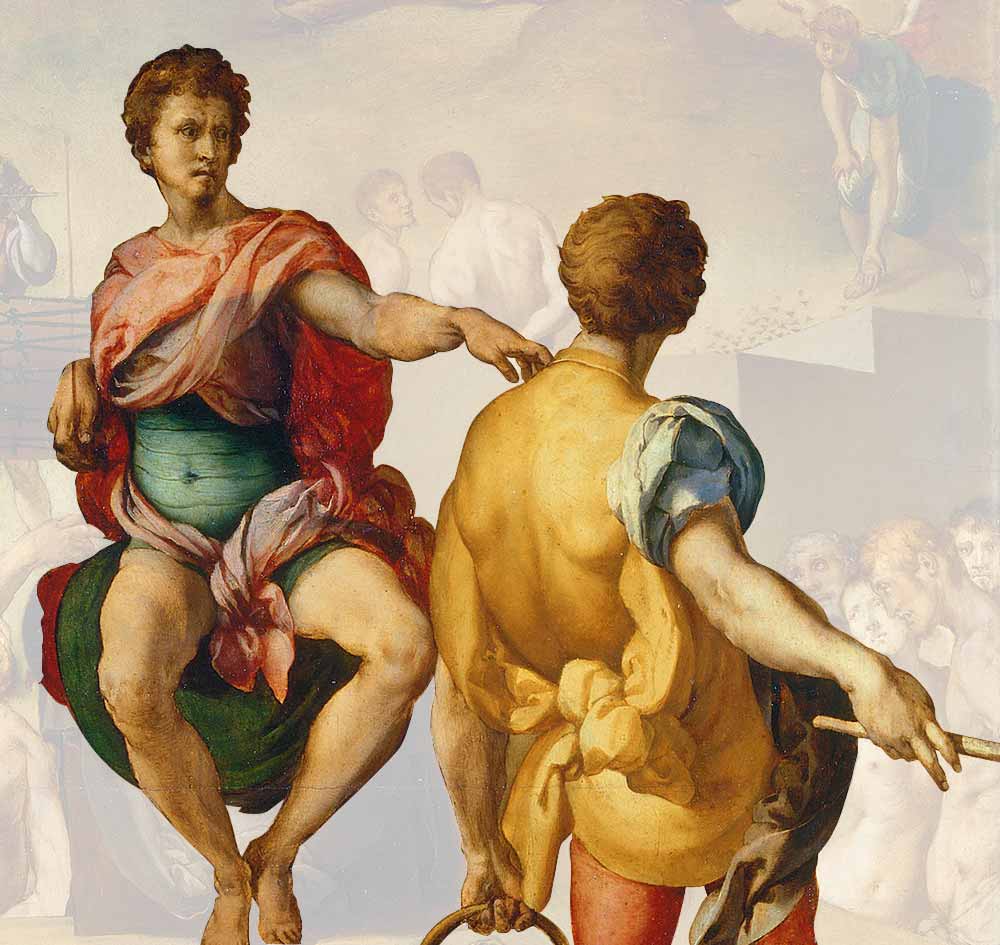

Naked bodies crawl on their knees, hang from crosses or writhe with pain. They are marked through and through by the terrible suffering that has befallen them. In this work of 1529/30 – which was also highly charged with political allusions – Pontormo concerned himself extensively with body language as an expression of human emotion.

The Medici played a decisive role in the power struggle over Florence from the fourteenth century onward. In 1527, influential citizens had revolted against the banker clan’s claim to exclusive power for the second time and driven them out of town. One reason for the Florentines’ infuriated uprising was the appropriation of funds from the trade city to finance the pope in Rome. The Medici banded together with the Habsburg emperor Charles V, who supported their return with his troops. Pope Clement VII, himself a Medici, likewise joined the party of the beleaguerers. Florence was compelled to surrender in 1530. Nearly half of the town population had fallen victim to the siege. The banished Medici son Alessandro returned to the city as the first duke.

Legend and reality

Pontormo’s Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand served to mirror the explosive events linked with the siege of Florence. A Medici, the painting implies, can be every bit as cruel and un-Christian as the antique emperor who tortured the soldiers under Achatius’s command for converting to the true faith.

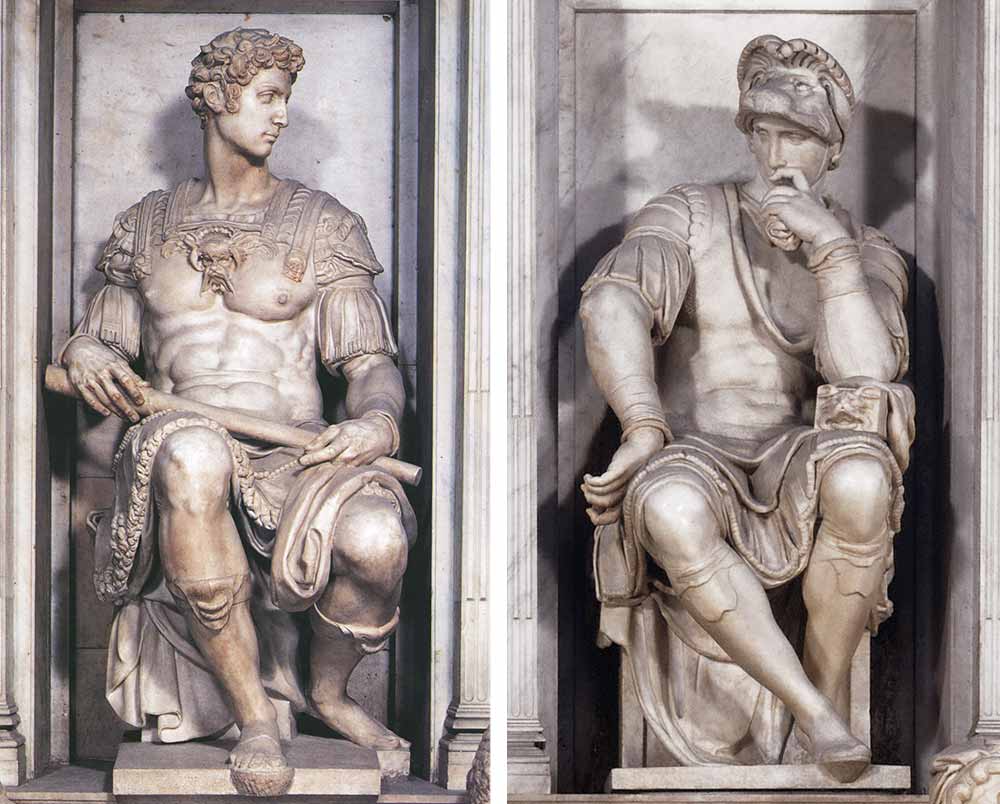

As a way of emphasizing the similarities between legend and reality, Pontormo availed himself of a clever artistic trick: the enthroned figure of the ruler in his painting suspiciously resembles the portrait figures of two famous Medici progeny. The marble sculptures of Lorenzo and Giuliano de’ Medici had been executed for the family’s Florentine burial chapel by the famous Michelangelo. In the armour worn by Roman captains, they sit on thrones of stone. Michelangelo’s sculptures were already famous at the time, and the resemblance between them and Pontormo’s motif of the brutal Roman ruler will certainly not have escaped the notice of the Florentine citizens.

The new duke

and his painter

An ambitious and alert leader: the gaze of the young Duke Alessandro de’ Medici rests on the city of Florence. Its silhouette – complete with the monumental dome of the cathedral – rises up on the distant horizon in full splendour.

Guarantor of a

Golden Age

Alessandro’s successor on the ducal throne was Cosimo de’ Medici. Pontormo presumably portrayed him here at the age of seventeen or eighteen – that is, shortly before he assumed power.

Under the reign of Cosimo I, the city blossomed as a centre of artistic production. He wanted Florence to gain new prestige in the area of culture. The town’s leading artistic figures were accordingly regular visitors to the ducal court. The ruler presented himself as a guardian of Florentine tradition, and the portraits he commissioned of himself and his family reflect the magnificence and pride of the Medici dynasty.

Aloof splendour

Cosimo de’ Medici’s young wife directs her aloof, cool gaze directly at the beholder. Eleonora di Toledo’s fair porcelain skin virtually radiates in contrast to the deep blue background.

Her dress corresponded to courtly fashions in her native Spain. Eleonora thus expressed her loyalty to the Holy Roman Empire of Emperor Charles V, who as Charles I was also the king of Spain. Her husband Cosimo I had him to thank for the dukedom that was a great source of pride to the Medici. Among her subjects, on the other hand, she was quite unpopular. She enjoyed her husband’s confidence, however, and stood in for him intermittently as a regent. She fostered the arts and, a devout Catholic, supported the founding of new churches.

A little

statesman

The three-year-old Garzia de’ Medici is depicted here with an unnaturally serious, almost statesman-like air. His skin is just as pale as his mother Eleonora’s.

The contest

of the arts

The foundation of academies in sixteenth-century Florence rendered the city a centre for the theoretical study of art.

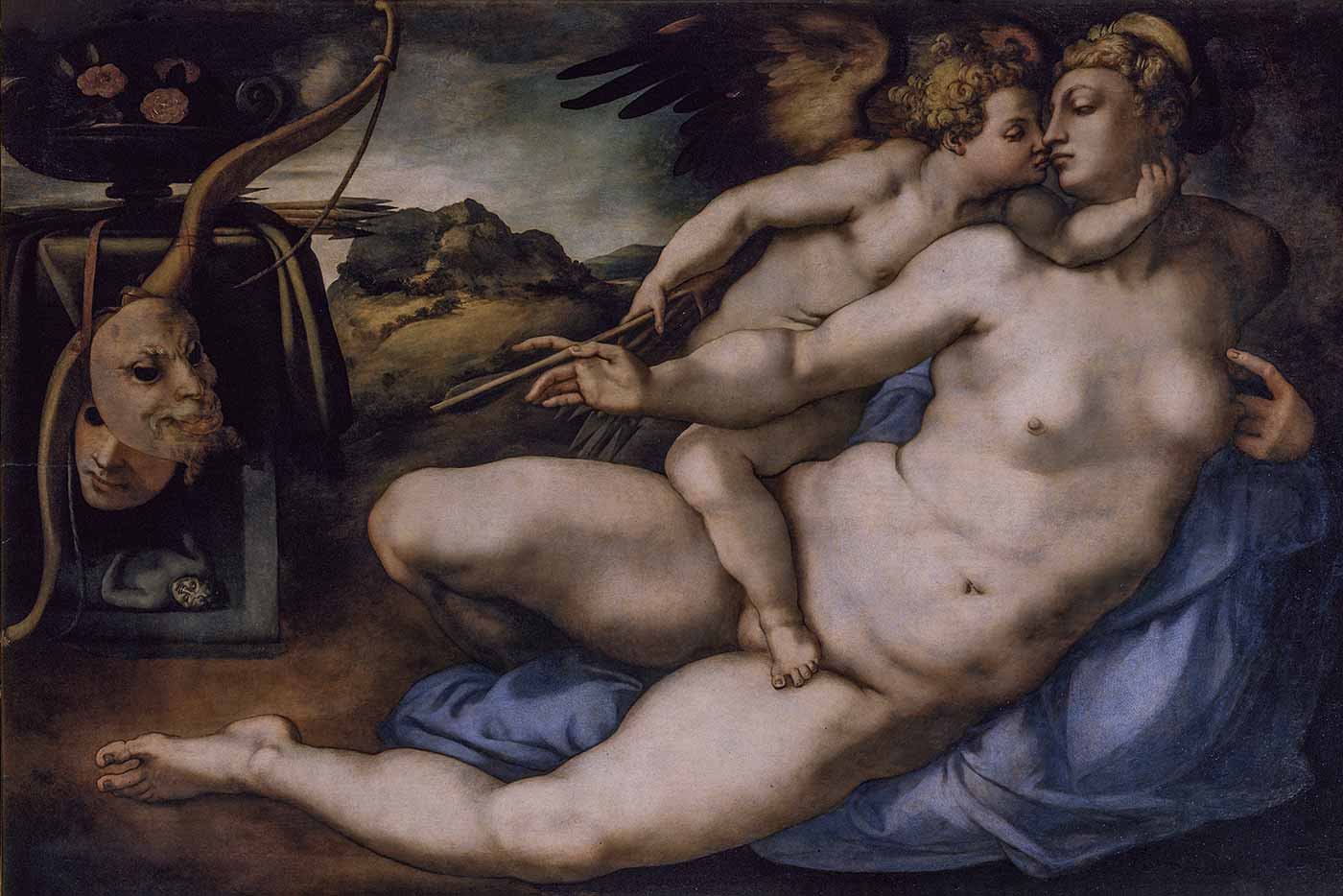

The game of deception

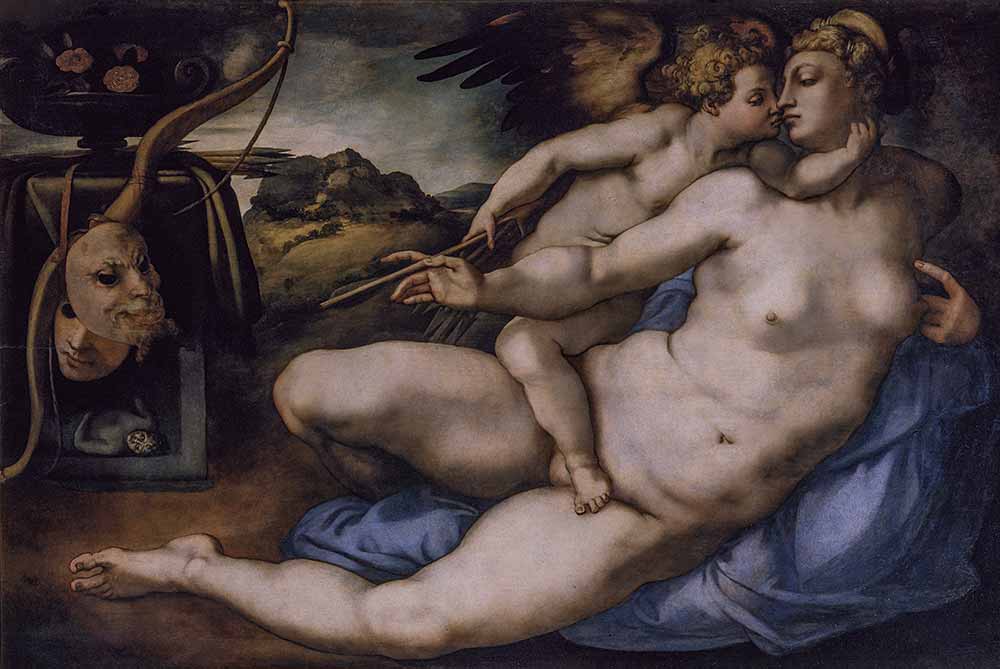

Cupid wraps his arm around the neck of his mother, Venus, the goddess of love. Apparently his aim is to distract her with a kiss, as his gaze wanders in the direction of his quiver. With his right hand he is removing an arrow.

Bringing sculpture to life

The sculptor Pygmalion has devoted his entire life to his work. One day, however, he falls in love with an ivory sculpture he has made of a beautiful woman.

Biblioteca

Laurenziana

A model of the vestibule of the Biblioteca Laurenziana was built especially for the exhibition. The library is considered a classic example of Mannerist architecture in Florence. A wall has been omitted in the model, allowing an instructive view of the imposing edifice.